Already when slavery was abolished in Great Britain in 1833, reparations were paid. The British state considered that the slave owners had to be compensated in some way for the brutal fact that they lost part of their property, which in this case consisted of people who gained their freedom. A clear signal as to which side had the biggest need for sympathies from the state.

After the decolonisation of Africa and the Cold War, the African Union started to pursue claims for reparations for slavery to the former slaves in the 1990s. They actually managed to bring up the issue on the agenda of the UN World Conference against Racism in Durban in 2001, known as “the Durban Conference”. It was, however, decided that all discussions regarding reparations would remain at discussion level, without concrete, binding decisions. Some days after the conference, the terror attacks in New York caught the world’s attention and the Durban Conference fell into oblivion. Already during the Durban Conference, the African Union was not only met by the West’s unwillingness to discuss reparations for slavery, slave trading and colonialism, but also by several other problems to create a united front and decide upon a concrete way forward.

In 2013, the member states of the Caribbean Community, CARICOM, revived the discussion on reparations for slavery. CARICOM contacted a British law firm in order to sort out the consequences of transatlantic slave trading and slavery. The consequences of the genocide of the Caribbean indigenous population and of colonialism were also investigated. These consequences were reported and summarised in ten points that CARICOM wants reparations for. CARICOM’s goal is to create a dialogue with the former slave trading European nations, in which they include Great Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden and Norway. CARICOM also threatened with suing these states in the International Court of Justice in case they were not ready to discuss the matter.

The heads of state of CARICOM’s members unanimously adopted a 10 point plan, listing direct consequences of the crimes committed by the abovementioned countries and that should be repaired. Most of the points require some sort of financial backing in order to heal the wounds of history. CARICOM also asks for a full formal apology from the nations that exploited slave trading, for their role in slave trading, a requirement that by itself does not require any financial backing. CARICOM also emphasises that they are not beggars asking for charity, but they rather want the slave trading colonial powers to take responsibility for the consequences of transatlantic slave trading. Other points in the ten point plan includes for example: a comprehensive health care programme in the Caribbean and the creation of an African knowledge programme in order to increase the understanding for the historical identity of people of colour in the Caribbean and to create cultural institutions dedicated to remembering slavery and genocide around the world.

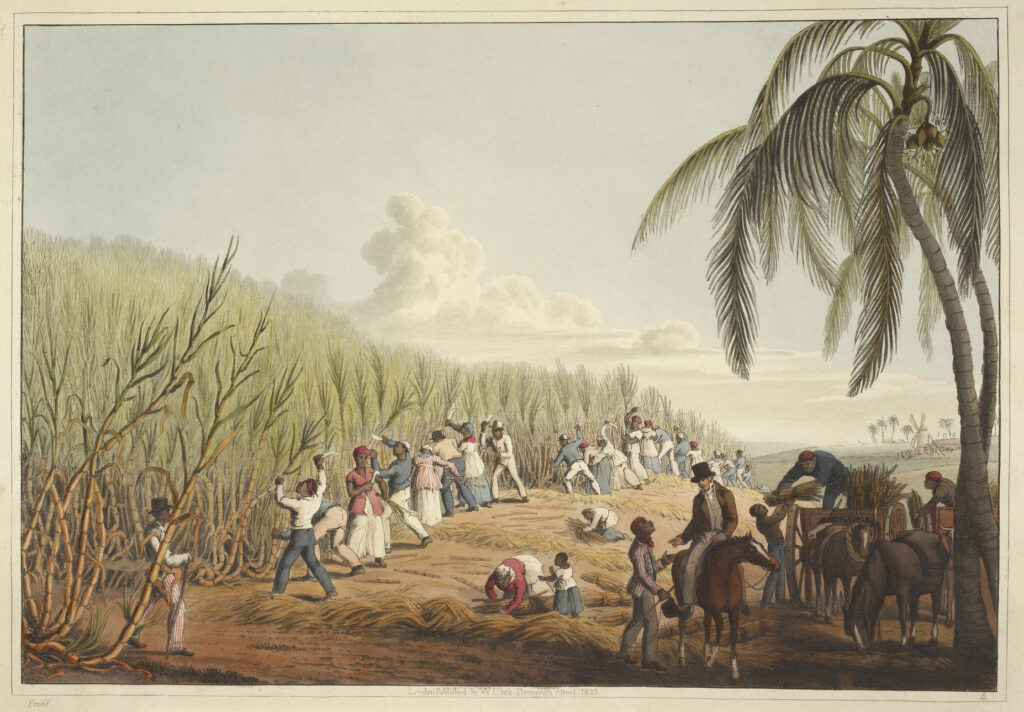

The history of slavery and slave trading is very much alive today, which is proven by CARICOM’s need to discuss this matter with the countries that have profited from slave trading and slavery. Western countries often overlook that it is not only a matter of monetary compensation, but that there is a deeper meaning in the claims; a wish to highlight the role of slaves in the construction of modern Europe. There is a willingness to highlight the suffering that slaves and their descendants have had to endure. At the same time, this concerns a part of history when racism has had very fertile soil.

There are different forms of use of history in the interpretation of the history of slavery, which creates the conflict we can see today. CARICOM founds its claim for reparations on moral, political and legal grounds. CARICOM practices a political, existential and moral use of history at the same time as the former slave trading powers have, so far, opposed reparations for slavery or ignored the claims. The explanation for this is that the former slave trading nations do not consider reparations for slavery to be the solution. On the contrary, these nations consider the history of slavery to be over and that we should not reopen this history book as it will only tear up old wounds. This attitude can be understood in different ways. It can be an active non-use of history, when one denies that one’s own history is related to the past. In a national context, such a way of thinking claims that the contemporary nation does not have anything to do with the nation that existed 200, 100, 50 or 10 years ago. It can also be understood as an interruption of historical consciousness, when one does not consider the past to affect us. Non-use of history can happen both consciously and unconsciously.

Eventually, political reasons may also be a determining factor. All of these reasons are likely to contribute to the conflict. The different parties exploit selected segments of history to argue for their cause without making progress, as the debate is stuck on the political level. The fact remains that there is a conflict regarding the history of slavery, in which the former slave colonies want to get their voice heard. The claim for reparations for slavery must be understood in this perspective. As long as this is not done, reparations for slavery will be a reasonable, even necessary, discussion in which historians can have a significant role.

MA John Degerlund

Åbo Akademi University